The article, "‘Literacy nooks’: Geosemiotics and domains of literacy in home spaces," written by Sophia Rainbird and Jennifer Rowsell (2014), discusses how home spaces have become networks of information sourcing and learning. Carving out interactive domains in the home, or creating a 'literacy nook,' maximizes learning opportunities and is also one way of asserting parental agency in their children's development. Rainbird and Rowsell suggest that parents construct learning environments, within the home space, for preschool children based on concepts of 'good' parenting. They explored how space is arranged and organized to produce an environment conducive to learning and development. Through four case studies of families in the US, they also found that the concept of good parenting differs from home to home according to socioeconomic, cultural, and class-based ideologies.

Traditional early childhood learning interventions originated from institutions providing literacy education to children in the classroom and encouraging parents to extend literacy learning into the home environment (pg. 215). Rainbirn and Rowsell want parents to be involved in literacy learning interventions by taking an active role in sourcing and securing information and resources into the home space. The idea of 'good parenting' in relation to literacy usually involves interactions around storybook reading in the home, more specifically, shared reading, picture books, and bedtime stories.

Building a learning environment consists of combining different elements - actors, environments, resources, and discourses - from which social meaning can be understood. We can gain a richer meaning about the sort of learning practices that occur in the home space when we consider these different elements together. In this article, Rainbirn and Rowsell considers the home space as the "social meaning construed from the material placement of the signs, discourses and actions within the home" (pg. 216).

Rainbirn and Rowsell analyzed parental spaces to see what 'good parenting' represents based on parents' descriptions of the use of their home space. They identified the following two characteristics:

- The nature of objects and artifacts used in the home tied to early childhood literacy (Is there a consumer presence in the home? Is there a deliberate eschewing of consumerism? Do parents have their own space?).

- The nature of childhood space (Is media present? Are books in close proximity and reach of a child? Is there comfortable seating for reading?).

Researchers took field visits to each of the four family's homes to get a sense of place and space. Observations of the use of home space were derived by mapping the space and recording the specific use areas for learning. Parents were also interviewed and asked to show researchers the books, magazines, information leaflets, DVDs, information technology and toys that they had collected, as well as how they were stored or displayed in the home. Rainbirn and Rowsell were particularly interested in the practices that occur in relation to the layout of the literacy spaces. They wanted to consider the relationship between these resources and home space.

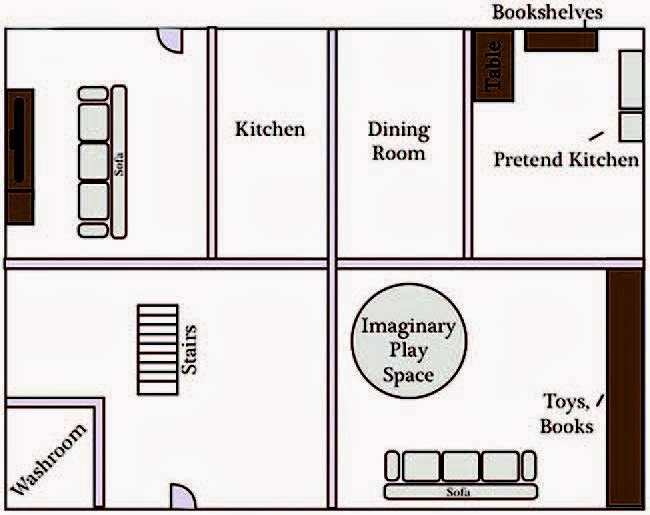

By creating visual maps, these researchers were able to show how space reflects philosophies of parental practice. The four homes represented a range from least child-ruled space to most child-ruled space. The fourth home was labeled as the most child-ruled space and was a large home with a very open plan and clear delineated spaces for their daughter. The father of this home is a firm believer in creativity and interpretative play and provides a large space for his daughter to engage in imaginative play. This reflects the idea of role playing as learning, which we have already learned a lot about this semester! The picture below shows the map of this father's house, where most of the right side of the house is space for his daughter.

Rainbird and Rowsell found that there was a distinct difference in the kinds of activities that were deemed

important according to gender. "[Mothers] tended to focus on the book

and its positioning spatially and within the household routine; the fathers, tended to focus more on personal interaction and literacy

learning through less traditional means in the home. Consequently, it could

be argued that mothers are more likely to be targeted with traditional methods

as to what constitutes good parenting through literacy learning in the home

(i.e. book reading), whereas the fathers’ notions of ‘good parenting’ are more

open to exploring methods such as family-centred time and imaginative play

that involves a different kind of literacy activity space" (pg. 229).

Paying close attention to the home space can provide us with a richer understanding of the kinds of literacy learning that takes place at home. "As the fluidity of home space creates a blurring of borders between designated learning spaces and family space, the kinds of learning that take place are also fluid as, for example, they blend into family routines" (pg. 230).

As a child, I never had a literacy nook, or a space carved out just for reading or activities, and I can only imagine how much more fun I could have had with literacy.

There are endless possibilities when it comes to creating a space just for learning! I've collected a couple of pictures from Pinterest just to give you an idea of how this simple space can be transformed into a whole world of its own.

Paying close attention to the home space can provide us with a richer understanding of the kinds of literacy learning that takes place at home. "As the fluidity of home space creates a blurring of borders between designated learning spaces and family space, the kinds of learning that take place are also fluid as, for example, they blend into family routines" (pg. 230).

As a child, I never had a literacy nook, or a space carved out just for reading or activities, and I can only imagine how much more fun I could have had with literacy.

There are endless possibilities when it comes to creating a space just for learning! I've collected a couple of pictures from Pinterest just to give you an idea of how this simple space can be transformed into a whole world of its own.

This is a closet remodeled into a reading nook.

This is an entire play room.

This is a small window space with books displayed just like at the bookstore!

'Literacy Nooks': Geosemiotics and domains of literacy in home spaces

Such an amazing article--it's clear that it's inspiring lots of good ideas and deep thinking about literacies!

ReplyDelete